Tomie dePaola’s picture book, Oliver Button is a Sissy, is the heroic story of Oliver Button, a young boy accused of being a “sissy” because he does not abide by the standards of his gender based on the ideological expectations of his peers, family and society. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word sissy as being an effeminate person; a coward. The particular use of language used to express the book’s theme differentiates the subject from most books intended for a young audience. Identity and gender is a sensitive subject to a developing child of only six or seven years. The title provides the reader with a pre-conceived notion about Oliver Button’s identity. DePaola’s small book is only 6” x 8” and discusses the delicate topic of gender and identity in an approachable way. In Words About Pictures, Perry Nodelman states, “We tend to read smaller books expecting charm and delicacy – and to find it even if it is not there” (Words 44). DePaola runs the risk of writing a book that might introduce a child’s vocabulary to a discriminating word like “sissy,” or characteristics of a person that may be perceived as a negative quality. Oliver Button is a clean-cut young boy who wears trousers and collared shirts. He differs from his peers who wear baseball caps and sporting accessories. However, the author writes an emotionally effective story that shows Oliver’s individuality as a positive quality that results in the protagonist’s victory.

Because Oliver Button doesn’t like to play sports, his parents urge him to exercise. He begins to take dance lessons and because of this, Oliver is taunted by his peers. The bullies write on the school wall, “OLIVER BUTTON IS A SISSY” (dePaola). Despite being slandered by the boys and “hav[ing] help from [the] girls,” Oliver “kept on going to Ms. Leah’s Dancing School every week.” Oliver steps into the spotlight and performs his tap routine at the school’s talent show in front of a full auditorium. Disappointed, he does not win first place in the show. Regardless, Oliver’s triumphs over his otherness when he returns to school and finds the school wall’s graffiti replaced with, “OLIVER BUTTON IS A STAR” (dePaolo).

The glossy paperback cover is depicted with a frame drawn around the edge of the front and compliments Nodelman’s idea that, “Many picture books depict objects that act as frames on their title pages, like doorways inviting viewers into another, different world” (Words 50). The reader will soon enter Oliver’s world that differs from the stereotypes of young boys. There is a discrepancy between the interior and exterior appearance. Oliver is drawn center stage of the cover sitting within a frame. The frame within a frame is placed underneath the large text of the title. The cover shows Oliver painting a picture with blue watercolors, sitting beside a small, orange, playful cat. The cat reappears on the title page alongside Oliver who is dressed in an elaborate feathered hat and cape. This is the last the reader will see of Oliver’s cat. Perhaps the use of animals on the cover and title page are used as a manipulative mechanism to entice a child to want to read the book. The cat is no longer seen physically, but instead, can be found in a drawing that hangs on the wall. Even then the cat is colored brown, not orange. The pictures have a deliberately repetitive pattern of teal, white, green and shades of brown. There is no hint of the exciting blue and orange colors from the cover. In Molly Bang’s “Ten Principles of Design,” she notes that, “We associate the same or similar colors much more strongly than we associate the same or similar shapes” (Bang 76). The strict use of colors in dePaola’s book allows Oliver to both blend in with the scene and also be in the spotlight. Oliver pops out of the pages because of his attire against the contrasting background. During his performance, Oliver wears a white suit with teal detail when he performs his successful tap dancing performance at the talent show. As Bang says, “We notice contrasts, or…contrast enables us to see (Bang 80).

Oliver Button’s story is portrayed in chronological fragments. The absence of chapters and page numbers indicate that this particular story is intended to be read in one sitting. The linear narrative is visualized within frames. Although Nodelman argues that “a frame around a picture makes it seem tidier, less energetic,” the frames within dePaola’s illustrations are not tidy and in contrast, are drawn imperfectly and shaky. The framed scenes are drawn with a medium used mostly by children: crayons. As a whole, the book looks as if it was illustrated by a child and displays no element of realism. Instead, the characters are depicted to look like rag dolls. The frames consistently take up most of the page except for Oliver’s performance. When Oliver is on stage, the page shows movement and action through quadrants of frames. Because Oliver is trapped within the ideologies of the world he lives in, it is appropriate that he should be trapped within the frames of the picture book.

Unlike the cover that is filled entirely with teal outside of its frame, the interior framed scenes are surrounded by white space. The text is neatly placed alternately above and below the picture. The font is neat, perfectly legible and simple. Only one page is picture-less with centered text rather than top or bottom placement. Bang explains, “The center of the page is the most effective center of attention” (Bang 62). This page is significant, for it reveals important information and is the shift in the story line. On this page, the reader learns the reasons why Oliver doesn’t want to play ball: “He wasn’t very good at it. He dropped the ball or struck out or didn’t run fast enough. And he was always the last person picked for any team” (dePaola).

According to Charlotte Huck’s “Books for Ages and Stages” in her book Children’s Literature, dePaola’s book is appropriate for ages six and seven. The book shares characteristics that correspond with Huck’s standards for this age. According to Huck, children of this age have a “continued interest in [their] own world, [and are] more curious about a wider range of things” (Huck 47). Oliver Button is illustrated as having different interests from what boys of his age are typically used to. Instead of playing sports, he endeavors an array of creative projects that range from picking flowers, to arts and crafts and finally, performing on stage. Oliver endures criticism and remains unswayed as he pursues his passions. Thus, Oliver expands his world through exploring a “wider range of things.” More so, the book “Shows curiosity about gender differences” (Huck 48). According to the Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data, Oliver Button is a Sissy is classified as fiction within the category of sex role[s] (dePaola). Simply stated throughout the text, Oliver Button strays from the assigned roles that boys play sports.

The controversial content of Oliver’s story is enforced through its visual connotations. Based on the text of the story, there is no proof that Oliver has effeminate or cowardly qualities. Oliver is described to “like to walk in the woods and play jump rope…He liked to read books and draw pictures (dePaola). Oliver prefers to use his creative nature rather than athletic ability. Oliver’s soft, physical qualities are revealed once the story is visualized. The depiction of Oliver Button “express[es] our assumptions of the metaphorical relationships between appearance and meaning” (Nodelman 49). The use of a derogatory adjective such as “sissy” indicates a particular bias point of view before one can discover for himself the meaning behind Oliver’s persistence in pursuing his own hobbies rather than what “boys are supposed to do” (dePaola).

Oliver’s father and peers represent the colonization of a particular attitude of gender. While Oliver is singing and dancing, Oliver’s papa interjects, “Oliver…Don’t be such a sissy! Go out and play baseball or football or basketball. Any kind of ball!” (dePaola). In other words, Papa submits to the notion that in order for his son to be a real man, Oliver needs to grow some balls. Oliver Button has Nodelman’s concept of “inherent femaleness.” She describes, “Whether male or female, adults often describe their dealings with children in language which manages to suggest something traditionally feminine about childhood, something traditionally masculine about adulthood” (The Other, 30). The role of the father in a boy’s life is enforced and used to influence the development of his manly, paternal side. However, because Oliver does not submit to the pressures of his father and peers, his story is subversive. Oliver Button Is a Sissy “express[s] the imaginative, unconventional, noncommercial view of the world in its simplest and purest form” (Lurie xi).

The Library of Congress summarizes dePaola’s story in a single sentence: “His classmates’ taunts don’t stop Oliver Button from doing what he likes best” (dePaula). This particular story was published in 1979, a significant year for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender history in which multiple protests and movements took place all over the world. Appropriately for the age of its readers, Oliver’s effeminate qualities are intended to express the importance of individuality portrayed through creativity. However, the underlying symbolism can easily be picked up easily by an older generation lived through the events. It is ironic that Oliver’s dad should urge him to “play any kind of ball,” as it is possible for his son to fulfill his father’s urgency by becoming gay, using the word’s double entendre.

Works Cited

Bang, Molly. Picture This, How Pictures Work. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2000. Print.

dePaola, Tomie. Oliver Button Is a Sissy. Orlando: Voyager Books, 1979. Print.

Huck, Charlotte. Children’s Literature, Ninth Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2007. Print.

Lurie, Alison. Don’t Tell the Grown-ups: Subversive Children’s Literature. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1990. Print.

Nodelman, Perry. “Literary Theory and Children’s Literature.” Children’s Literature

Association Quarterly. 17.1 (Spring 1992): 29.

Nodelman, Perry. Words about Pictures. Athens: University of Georgia, 1988. Print.

"Sissy." An effeminate person; a coward. 2. The Oxford English Dictionary, 2010. Web. 8 June 2010.

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Monday, September 27, 2010

Men Are Wolves: Sam Sham and the Pharaohs’s Li’l Red Riding Hood

Charles Perrault concludes his 1697 fairy tale Little Red Riding Hood with the moral that, “Not all wolves/ Are exactly the same” (Perrault). Both the Big Bad Wolf (BBW) of Sam Sham and the Pharaohs’s 1966 Billboard Hit, Li’l Red Riding Hood and Perrault’s Old Neighbor Wolf (ONW) share the same goal to devour Little Red Riding Hood (LRR) at grandma’s house. They differ, however, in their means to reach the end of the road. Old Neighbor Wolf races Little Red Riding Hood to grandma’s house, and the Big Bad Wolf distracts the young girl by dressing in a meek sheep suit in order to gain her trust. Perrault concludes, “Some are perfectly charming…tame wolves/ Are the most dangerous of all” (Perrault 13). Without the ideological knowledge of the fairy tale or epithets used to describe the wolves, neither BBW nor ONW offer a threatening demeanor. The Big Bad Wolf is a modernized example of Perrault’s warning. Adapted for its time, Sham turns a classical fairy tale into a contemporary rock and roll song moralized just the same.

Without pictures and with only words, Little Red Riding Hood becomes the protagonist and focal character of both stories. Perrault writes a complete, contextualized story. The reader learns that the young girl is named after “a little red hood [that was made] for her,” and she walks alone in the forest because she listens to her mother’s demand: “I want you to go and see how your grandmother is faring” (Perrault, 11-12). Contrasting, Sham’s song is a condensed story that provides its context through the title. The wolf is introduced by a howling sound in the distance.

Both Perrault’s story and Sham’s song engage their audience. In the classical tale, the third person narrator invites his reader to partake in the story when he describes Little Red Riding Hood as being “the prettiest [village girl] you can imagine” (Perrault 12). As if filling a missing piece of a puzzle, Perrault provides the information that is missing from the beginning of Sham’s song. Sham’s first person narrator, played by Big Bad Wolf, begins his story with a question: “Who’s that I see walkin’ in these woods?” (Sham). Though ONW meets LLR in the forest and the BBW meets her in the woods, the setting is established and the scene moves forward.

The epithet “Old Neighbor” used in Perrault’s story misleads the reader about the wolf’s intentions for the young girl. The word “old” has dual meaning: the wolf can be considered aged and non-threatening, or as a neighbor over a period of time. The reader is safe to assume that there is a bond of trust between the two characters. LRR should trust her neighbor, or “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18). The pseudonym used to describe the wolf suggests that he and the young girl have a pre-existing acquaintance. Without the provided exposition from the narrator that “It [is] dangerous to stop and listen to wolves,” the reader may not be able to predict the fatal outcome of the young girl (Perrault 12).

Sham also misleads his audience of his wolf’s identity. The song begins, “Hey there Little Red Riding Hood,/ You sure are looking good./ You’re everything a big bad wolf could want” (Sham). The language suggests that the wolf is speaking directly to LRR, or the words are his internal thought. In the fifth stanza, however, the audience discovers that the wolf is disguised and dressed in a sheep suit. Sheep, by nature, are timid and non-threatening. The wolf is alluding to the idea that sheep are the opposite of wolves and that by LRR staying near him, she is as safe as can be. The wolf assures her, “What a big heart I have – the better to love you with” (Sham). However, once the wolf announces that “I’m gonna keep my sheep suit on/ Until I'm sure that you've been shown/ That I can be trusted walking with you alone,” the meaning of the song changes entirely (Sham). It is at this point in the song that the duplicity in the language becomes evident. According to the 1945 Routledge Dictionary of Modern American slang and unconventional English, a wolf is a “sexually aggressive man.” The verb wolf is also a synonym for eating, and it can be used in a sexual connotation. What kind of wolf lurks underneath the sheep skin? Sham’s song is highly sexualized, and looking backward, Little Red Riding Hood’s fate is foreshadowed the moment the wolf spots her in the woods.

Old Neighbor Wolf continues to mask his identity, and Little Red Riding Hood is shocked by what she thinks are grandma’s big features. After ONW eats grandma, he takes her place in the bed. LRR arrives and listens to the wolf when he demands, “Climb into bed with me” (Perrault 12). She strips off of her clothes and joins the wolf in bed to have the famous back and forth dialogue. The girl says to the wolf, “Grandmother, what big eyes you have!” to which the wolf replies, “The better to see you with, my child” (Perrault 12). She finally says, “Grandmother, what big teeth you have!” and the wolf says, “The better to eat you with!” (Perrault 12). Without warning, the wolf “threw himself on Little Red Riding Hood” and she is eaten whole (Perrault 13). It is evident that the wolf’s big features were the warning that LRR did not catch onto and thus, she becomes the wolf’s dessert.

Sham’s song differs in storyline from Perrault’s classic tale. In Sham’s song the girl and wolf reverse roles. BBW describes LRR’s big features observing, “What big eyes you have. The kind of eyes that drive wolves mad…What full lips you have. They’re sure to lure someone bad” (Sham). Like LRR notices in Perrault’s tale, the wolf tells LRR that her large features as a bad thing. Because she has “Everything a big bad wolf could want,” the wolf cautions LRR about what is to happen to her and puts blame on her physical features that will cause her inevitable abduction. As both stories tell, it is dangerous to have big features.

Created three centuries apart from one another, the two versions of Little Red Riding Hood share a sexually explicit theme, as well as a life lesson for young girls: men can be deviant. The wolf in both stories is intended to have a dual identity. Both the song and the story deliberately depict the villain as literally being a wolf, however, both authors also give their wolf humanistic characteristics. Perrault’s moral warns young girls “Especially…Pretty, well-bred, and genteel” to beware of wolves with human characteristics such as being “perfectly charming…tame, pleasant and gentle” (Perrault 13). Because it is unlikely that a young woman of stature would frequent the forest and come into contact with wild animals, it is appropriate to interpret Perrault’s moral by acknowledging the duality in meaning of a wolf. Sham’s wolf exemplifies this idea. The wolf in a sheep suit says, “I'll try to be satisfied just to walk close by your side/ Maybe you'll see things my way before we get to grandma's place” (Sham). The BBW remains speaking in his charming way with hopes and anticipation to follow LRR to her chamber.

Fairy tales were established and evolved as a form of entertainment that was passed down orally. Much like the oral tradition, lyrics to popular music in America frequently tell a story. Because these epic tales were not found in written form until much later, an inevitable discrepancy exists in form, content and characters between the tales printed today. It is ironic that the cause of Perrault’s protagonist’s demise was due to listening to the wolf, suggesting that the stories told aloud should not be taken seriously. Perhaps Little Red Riding Hood of Sham’s song learns Perrault’s lesson. The BBW begs her, “Listen to me,” and it is possible that Little Red Riding Hood becomes a bigger person and gets to grandma’s without help (Sham).

Works Cited

Blackwell, Ron. (1966). Li'l Red Riding Hood [Sam Sham and the Pharaohs]. Li'l Red Riding Hood. MGM.

Perrault, Charles. "Little Red Riding Hood." The Classic Fairy Tales. Ed. Tatar, Maria. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1999. 11-13. Print.

Without pictures and with only words, Little Red Riding Hood becomes the protagonist and focal character of both stories. Perrault writes a complete, contextualized story. The reader learns that the young girl is named after “a little red hood [that was made] for her,” and she walks alone in the forest because she listens to her mother’s demand: “I want you to go and see how your grandmother is faring” (Perrault, 11-12). Contrasting, Sham’s song is a condensed story that provides its context through the title. The wolf is introduced by a howling sound in the distance.

Both Perrault’s story and Sham’s song engage their audience. In the classical tale, the third person narrator invites his reader to partake in the story when he describes Little Red Riding Hood as being “the prettiest [village girl] you can imagine” (Perrault 12). As if filling a missing piece of a puzzle, Perrault provides the information that is missing from the beginning of Sham’s song. Sham’s first person narrator, played by Big Bad Wolf, begins his story with a question: “Who’s that I see walkin’ in these woods?” (Sham). Though ONW meets LLR in the forest and the BBW meets her in the woods, the setting is established and the scene moves forward.

The epithet “Old Neighbor” used in Perrault’s story misleads the reader about the wolf’s intentions for the young girl. The word “old” has dual meaning: the wolf can be considered aged and non-threatening, or as a neighbor over a period of time. The reader is safe to assume that there is a bond of trust between the two characters. LRR should trust her neighbor, or “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18). The pseudonym used to describe the wolf suggests that he and the young girl have a pre-existing acquaintance. Without the provided exposition from the narrator that “It [is] dangerous to stop and listen to wolves,” the reader may not be able to predict the fatal outcome of the young girl (Perrault 12).

Sham also misleads his audience of his wolf’s identity. The song begins, “Hey there Little Red Riding Hood,/ You sure are looking good./ You’re everything a big bad wolf could want” (Sham). The language suggests that the wolf is speaking directly to LRR, or the words are his internal thought. In the fifth stanza, however, the audience discovers that the wolf is disguised and dressed in a sheep suit. Sheep, by nature, are timid and non-threatening. The wolf is alluding to the idea that sheep are the opposite of wolves and that by LRR staying near him, she is as safe as can be. The wolf assures her, “What a big heart I have – the better to love you with” (Sham). However, once the wolf announces that “I’m gonna keep my sheep suit on/ Until I'm sure that you've been shown/ That I can be trusted walking with you alone,” the meaning of the song changes entirely (Sham). It is at this point in the song that the duplicity in the language becomes evident. According to the 1945 Routledge Dictionary of Modern American slang and unconventional English, a wolf is a “sexually aggressive man.” The verb wolf is also a synonym for eating, and it can be used in a sexual connotation. What kind of wolf lurks underneath the sheep skin? Sham’s song is highly sexualized, and looking backward, Little Red Riding Hood’s fate is foreshadowed the moment the wolf spots her in the woods.

Old Neighbor Wolf continues to mask his identity, and Little Red Riding Hood is shocked by what she thinks are grandma’s big features. After ONW eats grandma, he takes her place in the bed. LRR arrives and listens to the wolf when he demands, “Climb into bed with me” (Perrault 12). She strips off of her clothes and joins the wolf in bed to have the famous back and forth dialogue. The girl says to the wolf, “Grandmother, what big eyes you have!” to which the wolf replies, “The better to see you with, my child” (Perrault 12). She finally says, “Grandmother, what big teeth you have!” and the wolf says, “The better to eat you with!” (Perrault 12). Without warning, the wolf “threw himself on Little Red Riding Hood” and she is eaten whole (Perrault 13). It is evident that the wolf’s big features were the warning that LRR did not catch onto and thus, she becomes the wolf’s dessert.

Sham’s song differs in storyline from Perrault’s classic tale. In Sham’s song the girl and wolf reverse roles. BBW describes LRR’s big features observing, “What big eyes you have. The kind of eyes that drive wolves mad…What full lips you have. They’re sure to lure someone bad” (Sham). Like LRR notices in Perrault’s tale, the wolf tells LRR that her large features as a bad thing. Because she has “Everything a big bad wolf could want,” the wolf cautions LRR about what is to happen to her and puts blame on her physical features that will cause her inevitable abduction. As both stories tell, it is dangerous to have big features.

Created three centuries apart from one another, the two versions of Little Red Riding Hood share a sexually explicit theme, as well as a life lesson for young girls: men can be deviant. The wolf in both stories is intended to have a dual identity. Both the song and the story deliberately depict the villain as literally being a wolf, however, both authors also give their wolf humanistic characteristics. Perrault’s moral warns young girls “Especially…Pretty, well-bred, and genteel” to beware of wolves with human characteristics such as being “perfectly charming…tame, pleasant and gentle” (Perrault 13). Because it is unlikely that a young woman of stature would frequent the forest and come into contact with wild animals, it is appropriate to interpret Perrault’s moral by acknowledging the duality in meaning of a wolf. Sham’s wolf exemplifies this idea. The wolf in a sheep suit says, “I'll try to be satisfied just to walk close by your side/ Maybe you'll see things my way before we get to grandma's place” (Sham). The BBW remains speaking in his charming way with hopes and anticipation to follow LRR to her chamber.

Fairy tales were established and evolved as a form of entertainment that was passed down orally. Much like the oral tradition, lyrics to popular music in America frequently tell a story. Because these epic tales were not found in written form until much later, an inevitable discrepancy exists in form, content and characters between the tales printed today. It is ironic that the cause of Perrault’s protagonist’s demise was due to listening to the wolf, suggesting that the stories told aloud should not be taken seriously. Perhaps Little Red Riding Hood of Sham’s song learns Perrault’s lesson. The BBW begs her, “Listen to me,” and it is possible that Little Red Riding Hood becomes a bigger person and gets to grandma’s without help (Sham).

Works Cited

Blackwell, Ron. (1966). Li'l Red Riding Hood [Sam Sham and the Pharaohs]. Li'l Red Riding Hood. MGM.

Perrault, Charles. "Little Red Riding Hood." The Classic Fairy Tales. Ed. Tatar, Maria. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1999. 11-13. Print.

Monday, May 17, 2010

Visibility as a Trap: JCVD, the Human Being Formerly Known as Jean Claude van Damme

Jean Claude van Damme presents himself in a whole new light in the 2008 film, JCVD. According to TIME Magazine, “He deserves not a black belt, but an Oscar.” Van Damme blurs his role as an international action movie star by acting in a role that his die-hard-fans are unfamiliar with: JCVD, the human being. What happens to an accomplished, wealthy, movie star when his identity is taken from him? What dwells beneath his biceps and beyond the realm of super-star mass destruction? What narrative is trapped behind his fame? Van Damme is blind to the fact that his life as a movie star is not a life at all. He will discover that his looks and stardom are merely signifiers of a concept called fame. When van Damme loses custody of his daughter and becomes a hostage in a robbery, the symbols of power that he possesses become useless and offer no value to his life. When van Damme is faced with the realities of an ordinary human being, he attunes his “awareness.” He comes to understand that the power and fame that once provided protection and glory are in actuality the limitations that control his life.

JCVD opens with an action-packed scene that encompasses Jacques Derrida’s idea of “différance.” For the first four minutes of the movie, Van Damme fights in a street battle against multiple men in one single shot of film. Derrida’s theory suggests that the men van Damme battles (referred to as “extras” in the movie industry) should be viewed “not [as] identities but [as] a network of relations between things whose differences from one another allows them to appear…separate and identifiable” (Rivkin 258). Van Damme fights through multiple attacks from dark and mysterious opponents. Van Damme makes his way through many obstacles such as unpredictable bursts of fire and spontaneous gunshots. The men he fights against are not identifiable causing the scene to be best described as, “a kind of ghost effect, a flickering of passing moments…They have no full, substantial presence (much as a flicking of cards of slightly different pictures of the same thing creates the effect of seeing the actual thing in motion)” (Rivkin 258). Like a deck of cards, though each warrior plays a role in the movie, each individual’s identity is arbitrary as they are all one in the same. Flicking a deck of cards is also reflective of a reel of film running through a projector, both serving as postmodern qualities. The action scene ends abruptly when a wall of the movie set falls over. The audience is watching reflexive cinema: a movie being filmed within a movie. This movie appears to take place in an Asian country. The director demands a retake. Van Damme is no longer idealized by the movie set and his true, aged self is exposed. On film, van Damme plays a muscular, impenetrable machine-like force, however, once the camera stops, van Damme must catch his breath and he admits to his limited capabilities. Van Damme declares, “It is very difficult for me to do everything in one shot. I am forty-seven years old!” Van Damme walks away from the scene with his head down in defeat.

The scene that follows takes place in an American court room. The audience draws this conclusion by the signs of a brightly-lit American flag and a gold-plated eagle plaque. Within the realm of the courtroom, it is apparent that van Damme is faced with the American Judicial “Panopticon.” According to Foucault, “The major effect of the Panopticon [is] to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power" (Foucault 554). Van Damme stands no chance of liberty as a French man inside of an American court room: the symbol for justice. Van Damme sits under the surveillance of the judge who sits in the “all seeing” seat of the circular room. As the hearing proceeds, the opposing attorney speaks ill of van Damme, illuminating him in an undesirable light. The attorney says, “My client is aware of the responsibilities of raising a child…On the other hand, we have an actor here who[‘s] entire career experience is with films…no responsible, aware parent would expose their children to…How does this actor play death? Let me count the ways.” Van Damme’s profession as an actor can not substitute his role as a parent, not are they interchangeable. The assumption of such is an example of what Derrida calls “supplement at the origin.” This idea refers to, “if one tries to grasp the presence of something, one encounters a difference, not something substantial” (Rivkin 259). The attorney uses the logical fallacy, ad hominem, by judging Van Damme’s character based on his profession. This fallacy also violates Derrida’s idea that, “either the [signs, or identities] represent an idea which they signify in order to mean something, or, they must substitute for the presence of an object in the world that they designate” (Rivkin 258). What does the lawyer mean when he emphasizes the word, “awareness”? In the spirit of a postmodern screenplay, the importance of self-awareness is the most appropriate in. It is ironic that van Damme should be accused of lacking self-awareness based on the sole fact that he is an actor in violent films when his profession provides the means to feed his family. Simultaneously, van Damme lacks awareness in his ability to see past what he already knows. Van Damme “is seen, but he does not see” (Foucault).

The action of the film takes place in van Damme’s native country of France where his loyal fans reside. Van Damn is threatened to be fired by his own attorney unless he wires money to pay for his lawyer fees. In a rush to get to the “post office,” van Damme is distracted by two young men that rush from a video store to meet him. The young men capture the moment by taking photos with the actor, reflective as another means of portraying van Damme’s life under surveillance. Van Damme is able to break from the men and head toward the post office; he escapes the frame for a moment. The young men show off their digital photographs to a police officer and the three of them join in praise toward the actor. One of the men says at random, “Aware!” Within moments, a gunshot shatters the window of cab and the people in the streets begin to panic. The loud noise acts as an attribute of a postmodern text forcing the audience to be shaken from their focus and start again. The movie can be categorized (nonexclusively) as a mystery, for the audience knows nothing about the source of the gun shot. When the shock of the bullet dies down for the audience, the silent air is replaced with instrumental detective music. Like traits of a postmodern text, the movie’s story unravels out of sequence. As the question of where the bullet comes from remains a mystery, the screen turns black and the following phrase appears: “1. La Réponse avant la Question.” Intentionally implemented by the director are English subtitles beneath the phrase: “1. The Answer before the question.”

The frame changes to focus on the police man running toward the post office. He comes face to face with van Damme, however, van Damme stands behind a glass window. The window’s reflect casts a glare that makes van Damn appear be behind bars. To the audience, van Damn looks like a potential perpetrator in the unsolved mystery. In his essay, “On Truth and Lying in an Extra-moral Sense,” Friedrich Nietzsche writes, “What indeed does man know about himself? Oh! that he could but once see himself complete, placed as it were in an illuminated glass case!” (Nietzsche). Is it possible that the illusion of van Damme behind bars can signify inner completeness? The audience is redirected to the interior of the building and the truth of the mystery begins to reveal itself. Prior to van Damme’s entrance, the post office was in the midst of being robbed independent of van Damme. By chance, van Damme forces himself into an active robbery by pressuring Arthur, one of the conmen to let him into the building. Once van Damme enters and discovers that he has become a hostage, the robbers make use of his identity and set him up to be perceived at the criminal. Van Damme becomes the liaison between the robbers and the outside authority.

Van Damn does not rebel against the robbers when they demand him to act as the leading criminal with the understanding that, “A real subjection is born mechanically from a fictitious relation. So it is not necessary to use force to constrain the convict to good behavior” (555). Van Damme cannot control the impulses of the psychopaths within the Ponopticon, but he can appease the situation so as to manipulate it. Van Damme intends to find away to free the hostages as he later suggests to Arthur, "We gotta free the hostages.” With this intention, van Damme’s awareness begins to develop. He adheres to the requests of the robbers in order to create a “fictitious” relationship. Outside of the post office, a large crowd has surfaced believing that van Damme is the responsible party for the hostage situation. The Chief of police persuades Van Damme’s mother to manipulate her son into freeing one of the hostages. The robbers allow this to happen and they release the single mother from the building, but keep her child captive. The chief of police rush toward the building when his fellow officers announce that, “They are raising the curtain!” In the English language, a curtain is defined as: “The screen separating the stage from the auditorium, which is drawn up at the beginning and dropped at the end of the play or of a separate act” (O.E.D.). To a native English speaker, the raising of a curtain signifies the beginning of a live performance. In the movie, however, a gate is opened, not a piece of drapery. Gate is defined as, “An opening in a wall, made for the purpose of entrance and exit, and capable of being closed by a movable barrier…or the enclosure-wall of a large building (O.E.D.). There exists a strong disconnection between the symbols. They both serve the purpose of acting as a barrier between the internal and the external, however, what purpose does the word choice signify? The Popticon of the moment is the post office with an all seeing eye in the large crowd of people. Foucault explains that the Ponopticon is “like so many cages, so many small theaters in which each actor is alone, perfectly individualized and constantly visible...It reveres the principle of the dungeon; or rather of its three functions – to enclose, to deprive of light, and to hide – it perseveres only the first and eliminates the other two. Full lighting and the eye of a supervisor capture better than darkness, which ultimately protected. Visibility is a trap" (Foucault 554). Are curtains and gates intended to be substitutions and/ or interchangeable? Is van Damme putting on a show for his fans to see? Van Damme breaks the fourth wall and looks directly into the camera. Filled with tears, van Damme rids himself of any fear of vulnerability and delivers a monologue to the audience. His self reflexive, stream-like consciousness confesses his inner feelings toward his life, its meaning and his current situation.

Van Damme acknowledges his decision to submit his life and body to the power relations of Hollywood when he transformed or “invested” his body from being “small and scrawny” into a fit form filled will the muscles that will be the defining feature of his fame. His body is “Under a regime of controlled consumption shaped by marketing and advertising, to consume signs of status or of self identity” (Rivkin). During his monologue, van Damme shows resentment toward Hollywood for his constructed identity and mourns the loss of the things he once loved. He says, “I took up karate…"Oss!" It's Samurai code. It's honour, no lies…In the US…No one says "Oss" to you. Sometimes people in show business say, "We're gonna' fuck em.'" I believed in…the Dojo.” The passion and inspiration he once found in Karate becomes one of the many signifiers for popular culture and trends. Van Damme expresses his disappointment in the “différance” that has developed within his field of fighting. Van Damme continues, “I went from poor to rich and thought, ‘why aren't we all like me, why all the privileges? I'm just a regular guy…It's not my fault if I was cut out to be a star…I asked for it, really believed in it.” The evolution of van Damme’s life exemplifies Foucalt’s concept of power relations. Van Damme becomes empowered by his fame in Hollywood, however, “This power is not exercised simply as an obligation or a prohibition on those who 'do not have it'; it invests them, is transmitted by them and through them” (Foucault). Van Damme encompasses the nature by which power relations exist: just as the subject submits the force of power, the institution also “exert[s] pressure upon the [subject]" (Foucault). Van Damme willingly resists the force that has controlled his life for so long. At this moment, he is willing to sacrifice his power for the total ownership of himself and his life. Van Damme concludes, “What I've done on this Earth. Nothing! I've done nothing!...I truly believe it's not a movie. It's real life. Real life…It's hard for me to judge people and it's hard for them... not to judge me. Easier to blame me. Yeah, something like that.” Van Damme becomes “aware” and “assumes responsibility for the constraints of power [that] he makes them play spontaneously upon himself” (Foucault 556). Van Damme’s tears are convincing, however, the reality for the audience is that they are watching a performance, not real life. The camera zooms out of the bust shot of van Damme and an aerial view films the actor downward as he floats into a seat within his reality. As if he listened to the entire monologue, Arthur stands still, staring at van Damme with an intense look of astonishment and sympathy.

Van Damme lives his life under constant surveillance. For ninety-seven minutes, he is being watched from every side of the spectrum, especially the fourth wall. The audience serves as a reminder to van Damme of his restricted lifestyle and at the same time, the viewer is constantly reminded to be self-aware. With twists, turns, bangs and silence, the director intends to shift the environment for the viewer as a means to remind the viewer of its purpose: watch the movie, do not be immersed in it. However, is the audience watching a film of van Damme’s reality, or are we merely being entertained?

Van Damme’s shift in genre is influential to his Hollywood-made identity. In JCVD, he deconstructs this so-called identity and no longer limits himself to be defined based on a genre of film. Instead, he chooses to be undefined and behave an ordinary person. When his life slips from his hands and he loses custody of his daughter, all of his money and is threatened for his life, van Damme is finally “aware” of the constructed identity he stood by for so long. He chooses to abandon his identity because has no truth value. How can one be identified through signs of material in death? Van Damn invests his entire life in Hollywood, only to come out empty handed. It is Hollywood where he loses himself, and it is not until his jail sentence that he becomes “aware” of his self-prescribed “power relation in which he simultaneously plays both roles; he becomes the principle of his own subjection” instead of something outside of himself (Foucault). Thus, van Damme is removed from the Ponopticon of Hollywood and the public eye, and placed into prison. While serving his term in jail, van Damme uses his Hollywood identity to reinvent his pure passion for Karate. Van Damme creates value in his immediate environment through teaching Karate to his fellow inmates. In the finals moments of the movie, the aged actor is visited by his daughter while in jail. Van Damme sits across the table from her, separated by a glass window. At this moment, the audience sees van Damme smile genuinely for the first time. He does not look to any camera or put on any kind of show, but looks directly at his daughter and finds happiness in his state of being undefined. Nietzsche writes, “Only by means of forgetfulness can man ever arrive at imagining that he possesses ‘truth’” (Nietzsche). Perhaps the reflection in the window from the beginning of the movie was a premonition for his future. Van Damme finds his complete self within a “glass case” and behind bars. Nietzsche concludes, "Only by the invincible faith, that this sun, this window, this table is a truth in itself: in short, only by the fact that man forgets himself as subject, and what is more as an artistically creating subject: only by all this does he live with some repose, safety, and consequence. If he were able to get out of the prison walls of this faith, even for an instant only, his 'self-consciousness' would be destroyed at once" (Nietzsche). Jean Claude van Damme successfully finds the “awareness” he has lost for so long once he is able to see through the glass to his true reflection.

Foucault, Michel. “Discipline and Punish.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 549-565. Print.

JCVD. Dir. Mabrouk El Mechri. Perf. Jean Claude van Damme. Peacearch, 2008. DVD.

Lyotard, Jean-François. “The Postmodern Condition.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 355-364. Print.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. “On Truth and Lying in an Extra-moral Sense.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 262-265. Print.

Rivkin, Julie and Michael Ryan. “Introduction: Introductory Deconstruction.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 257-261. Print.

JCVD opens with an action-packed scene that encompasses Jacques Derrida’s idea of “différance.” For the first four minutes of the movie, Van Damme fights in a street battle against multiple men in one single shot of film. Derrida’s theory suggests that the men van Damme battles (referred to as “extras” in the movie industry) should be viewed “not [as] identities but [as] a network of relations between things whose differences from one another allows them to appear…separate and identifiable” (Rivkin 258). Van Damme fights through multiple attacks from dark and mysterious opponents. Van Damme makes his way through many obstacles such as unpredictable bursts of fire and spontaneous gunshots. The men he fights against are not identifiable causing the scene to be best described as, “a kind of ghost effect, a flickering of passing moments…They have no full, substantial presence (much as a flicking of cards of slightly different pictures of the same thing creates the effect of seeing the actual thing in motion)” (Rivkin 258). Like a deck of cards, though each warrior plays a role in the movie, each individual’s identity is arbitrary as they are all one in the same. Flicking a deck of cards is also reflective of a reel of film running through a projector, both serving as postmodern qualities. The action scene ends abruptly when a wall of the movie set falls over. The audience is watching reflexive cinema: a movie being filmed within a movie. This movie appears to take place in an Asian country. The director demands a retake. Van Damme is no longer idealized by the movie set and his true, aged self is exposed. On film, van Damme plays a muscular, impenetrable machine-like force, however, once the camera stops, van Damme must catch his breath and he admits to his limited capabilities. Van Damme declares, “It is very difficult for me to do everything in one shot. I am forty-seven years old!” Van Damme walks away from the scene with his head down in defeat.

The scene that follows takes place in an American court room. The audience draws this conclusion by the signs of a brightly-lit American flag and a gold-plated eagle plaque. Within the realm of the courtroom, it is apparent that van Damme is faced with the American Judicial “Panopticon.” According to Foucault, “The major effect of the Panopticon [is] to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power" (Foucault 554). Van Damme stands no chance of liberty as a French man inside of an American court room: the symbol for justice. Van Damme sits under the surveillance of the judge who sits in the “all seeing” seat of the circular room. As the hearing proceeds, the opposing attorney speaks ill of van Damme, illuminating him in an undesirable light. The attorney says, “My client is aware of the responsibilities of raising a child…On the other hand, we have an actor here who[‘s] entire career experience is with films…no responsible, aware parent would expose their children to…How does this actor play death? Let me count the ways.” Van Damme’s profession as an actor can not substitute his role as a parent, not are they interchangeable. The assumption of such is an example of what Derrida calls “supplement at the origin.” This idea refers to, “if one tries to grasp the presence of something, one encounters a difference, not something substantial” (Rivkin 259). The attorney uses the logical fallacy, ad hominem, by judging Van Damme’s character based on his profession. This fallacy also violates Derrida’s idea that, “either the [signs, or identities] represent an idea which they signify in order to mean something, or, they must substitute for the presence of an object in the world that they designate” (Rivkin 258). What does the lawyer mean when he emphasizes the word, “awareness”? In the spirit of a postmodern screenplay, the importance of self-awareness is the most appropriate in. It is ironic that van Damme should be accused of lacking self-awareness based on the sole fact that he is an actor in violent films when his profession provides the means to feed his family. Simultaneously, van Damme lacks awareness in his ability to see past what he already knows. Van Damme “is seen, but he does not see” (Foucault).

The action of the film takes place in van Damme’s native country of France where his loyal fans reside. Van Damn is threatened to be fired by his own attorney unless he wires money to pay for his lawyer fees. In a rush to get to the “post office,” van Damme is distracted by two young men that rush from a video store to meet him. The young men capture the moment by taking photos with the actor, reflective as another means of portraying van Damme’s life under surveillance. Van Damme is able to break from the men and head toward the post office; he escapes the frame for a moment. The young men show off their digital photographs to a police officer and the three of them join in praise toward the actor. One of the men says at random, “Aware!” Within moments, a gunshot shatters the window of cab and the people in the streets begin to panic. The loud noise acts as an attribute of a postmodern text forcing the audience to be shaken from their focus and start again. The movie can be categorized (nonexclusively) as a mystery, for the audience knows nothing about the source of the gun shot. When the shock of the bullet dies down for the audience, the silent air is replaced with instrumental detective music. Like traits of a postmodern text, the movie’s story unravels out of sequence. As the question of where the bullet comes from remains a mystery, the screen turns black and the following phrase appears: “1. La Réponse avant la Question.” Intentionally implemented by the director are English subtitles beneath the phrase: “1. The Answer before the question.”

The frame changes to focus on the police man running toward the post office. He comes face to face with van Damme, however, van Damme stands behind a glass window. The window’s reflect casts a glare that makes van Damn appear be behind bars. To the audience, van Damn looks like a potential perpetrator in the unsolved mystery. In his essay, “On Truth and Lying in an Extra-moral Sense,” Friedrich Nietzsche writes, “What indeed does man know about himself? Oh! that he could but once see himself complete, placed as it were in an illuminated glass case!” (Nietzsche). Is it possible that the illusion of van Damme behind bars can signify inner completeness? The audience is redirected to the interior of the building and the truth of the mystery begins to reveal itself. Prior to van Damme’s entrance, the post office was in the midst of being robbed independent of van Damme. By chance, van Damme forces himself into an active robbery by pressuring Arthur, one of the conmen to let him into the building. Once van Damme enters and discovers that he has become a hostage, the robbers make use of his identity and set him up to be perceived at the criminal. Van Damme becomes the liaison between the robbers and the outside authority.

Van Damn does not rebel against the robbers when they demand him to act as the leading criminal with the understanding that, “A real subjection is born mechanically from a fictitious relation. So it is not necessary to use force to constrain the convict to good behavior” (555). Van Damme cannot control the impulses of the psychopaths within the Ponopticon, but he can appease the situation so as to manipulate it. Van Damme intends to find away to free the hostages as he later suggests to Arthur, "We gotta free the hostages.” With this intention, van Damme’s awareness begins to develop. He adheres to the requests of the robbers in order to create a “fictitious” relationship. Outside of the post office, a large crowd has surfaced believing that van Damme is the responsible party for the hostage situation. The Chief of police persuades Van Damme’s mother to manipulate her son into freeing one of the hostages. The robbers allow this to happen and they release the single mother from the building, but keep her child captive. The chief of police rush toward the building when his fellow officers announce that, “They are raising the curtain!” In the English language, a curtain is defined as: “The screen separating the stage from the auditorium, which is drawn up at the beginning and dropped at the end of the play or of a separate act” (O.E.D.). To a native English speaker, the raising of a curtain signifies the beginning of a live performance. In the movie, however, a gate is opened, not a piece of drapery. Gate is defined as, “An opening in a wall, made for the purpose of entrance and exit, and capable of being closed by a movable barrier…or the enclosure-wall of a large building (O.E.D.). There exists a strong disconnection between the symbols. They both serve the purpose of acting as a barrier between the internal and the external, however, what purpose does the word choice signify? The Popticon of the moment is the post office with an all seeing eye in the large crowd of people. Foucault explains that the Ponopticon is “like so many cages, so many small theaters in which each actor is alone, perfectly individualized and constantly visible...It reveres the principle of the dungeon; or rather of its three functions – to enclose, to deprive of light, and to hide – it perseveres only the first and eliminates the other two. Full lighting and the eye of a supervisor capture better than darkness, which ultimately protected. Visibility is a trap" (Foucault 554). Are curtains and gates intended to be substitutions and/ or interchangeable? Is van Damme putting on a show for his fans to see? Van Damme breaks the fourth wall and looks directly into the camera. Filled with tears, van Damme rids himself of any fear of vulnerability and delivers a monologue to the audience. His self reflexive, stream-like consciousness confesses his inner feelings toward his life, its meaning and his current situation.

Van Damme acknowledges his decision to submit his life and body to the power relations of Hollywood when he transformed or “invested” his body from being “small and scrawny” into a fit form filled will the muscles that will be the defining feature of his fame. His body is “Under a regime of controlled consumption shaped by marketing and advertising, to consume signs of status or of self identity” (Rivkin). During his monologue, van Damme shows resentment toward Hollywood for his constructed identity and mourns the loss of the things he once loved. He says, “I took up karate…"Oss!" It's Samurai code. It's honour, no lies…In the US…No one says "Oss" to you. Sometimes people in show business say, "We're gonna' fuck em.'" I believed in…the Dojo.” The passion and inspiration he once found in Karate becomes one of the many signifiers for popular culture and trends. Van Damme expresses his disappointment in the “différance” that has developed within his field of fighting. Van Damme continues, “I went from poor to rich and thought, ‘why aren't we all like me, why all the privileges? I'm just a regular guy…It's not my fault if I was cut out to be a star…I asked for it, really believed in it.” The evolution of van Damme’s life exemplifies Foucalt’s concept of power relations. Van Damme becomes empowered by his fame in Hollywood, however, “This power is not exercised simply as an obligation or a prohibition on those who 'do not have it'; it invests them, is transmitted by them and through them” (Foucault). Van Damme encompasses the nature by which power relations exist: just as the subject submits the force of power, the institution also “exert[s] pressure upon the [subject]" (Foucault). Van Damme willingly resists the force that has controlled his life for so long. At this moment, he is willing to sacrifice his power for the total ownership of himself and his life. Van Damme concludes, “What I've done on this Earth. Nothing! I've done nothing!...I truly believe it's not a movie. It's real life. Real life…It's hard for me to judge people and it's hard for them... not to judge me. Easier to blame me. Yeah, something like that.” Van Damme becomes “aware” and “assumes responsibility for the constraints of power [that] he makes them play spontaneously upon himself” (Foucault 556). Van Damme’s tears are convincing, however, the reality for the audience is that they are watching a performance, not real life. The camera zooms out of the bust shot of van Damme and an aerial view films the actor downward as he floats into a seat within his reality. As if he listened to the entire monologue, Arthur stands still, staring at van Damme with an intense look of astonishment and sympathy.

Van Damme lives his life under constant surveillance. For ninety-seven minutes, he is being watched from every side of the spectrum, especially the fourth wall. The audience serves as a reminder to van Damme of his restricted lifestyle and at the same time, the viewer is constantly reminded to be self-aware. With twists, turns, bangs and silence, the director intends to shift the environment for the viewer as a means to remind the viewer of its purpose: watch the movie, do not be immersed in it. However, is the audience watching a film of van Damme’s reality, or are we merely being entertained?

Van Damme’s shift in genre is influential to his Hollywood-made identity. In JCVD, he deconstructs this so-called identity and no longer limits himself to be defined based on a genre of film. Instead, he chooses to be undefined and behave an ordinary person. When his life slips from his hands and he loses custody of his daughter, all of his money and is threatened for his life, van Damme is finally “aware” of the constructed identity he stood by for so long. He chooses to abandon his identity because has no truth value. How can one be identified through signs of material in death? Van Damn invests his entire life in Hollywood, only to come out empty handed. It is Hollywood where he loses himself, and it is not until his jail sentence that he becomes “aware” of his self-prescribed “power relation in which he simultaneously plays both roles; he becomes the principle of his own subjection” instead of something outside of himself (Foucault). Thus, van Damme is removed from the Ponopticon of Hollywood and the public eye, and placed into prison. While serving his term in jail, van Damme uses his Hollywood identity to reinvent his pure passion for Karate. Van Damme creates value in his immediate environment through teaching Karate to his fellow inmates. In the finals moments of the movie, the aged actor is visited by his daughter while in jail. Van Damme sits across the table from her, separated by a glass window. At this moment, the audience sees van Damme smile genuinely for the first time. He does not look to any camera or put on any kind of show, but looks directly at his daughter and finds happiness in his state of being undefined. Nietzsche writes, “Only by means of forgetfulness can man ever arrive at imagining that he possesses ‘truth’” (Nietzsche). Perhaps the reflection in the window from the beginning of the movie was a premonition for his future. Van Damme finds his complete self within a “glass case” and behind bars. Nietzsche concludes, "Only by the invincible faith, that this sun, this window, this table is a truth in itself: in short, only by the fact that man forgets himself as subject, and what is more as an artistically creating subject: only by all this does he live with some repose, safety, and consequence. If he were able to get out of the prison walls of this faith, even for an instant only, his 'self-consciousness' would be destroyed at once" (Nietzsche). Jean Claude van Damme successfully finds the “awareness” he has lost for so long once he is able to see through the glass to his true reflection.

Works Cited

Foucault, Michel. “Discipline and Punish.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 549-565. Print.

JCVD. Dir. Mabrouk El Mechri. Perf. Jean Claude van Damme. Peacearch, 2008. DVD.

Lyotard, Jean-François. “The Postmodern Condition.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 355-364. Print.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. “On Truth and Lying in an Extra-moral Sense.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 262-265. Print.

Rivkin, Julie and Michael Ryan. “Introduction: Introductory Deconstruction.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 257-261. Print.

Thursday, April 29, 2010

Venus Emerging From Herself: A Postmodern Interpretation

Yesterday's group presentation was on Postmodern Theory. The class was given construction paper and chalk to create a modern interpretation of Botticelli's "The Birth of Venus" (See painting below).

Ancient Mythology teaches that Venus was born from the Sky and Sea. The angel-like figures on either side of the goddess represent those two elements as she emerges into the world. Venus is said to represent motherhood.

In my modernized drawing (see below), I have depicted Venus's birth on a hospital bed. I have depicted Venus to be born by a human-like figure. The ruching sheets by her feet resemble the pearl shell she stands upon in the painting. The newborn baby flies out of her mother's womb and cries in an unfamiliar realm.

In my modernized drawing (see below), I have depicted Venus's birth on a hospital bed. I have depicted Venus to be born by a human-like figure. The ruching sheets by her feet resemble the pearl shell she stands upon in the painting. The newborn baby flies out of her mother's womb and cries in an unfamiliar realm.

With doctors on either side of her, perhaps the mother birthing on the bed is self-reflective (a postmodern quality) and Venus is birthed from herself, or emerging from the Sky and Sea.

Ancient Mythology teaches that Venus was born from the Sky and Sea. The angel-like figures on either side of the goddess represent those two elements as she emerges into the world. Venus is said to represent motherhood.

In my modernized drawing (see below), I have depicted Venus's birth on a hospital bed. I have depicted Venus to be born by a human-like figure. The ruching sheets by her feet resemble the pearl shell she stands upon in the painting. The newborn baby flies out of her mother's womb and cries in an unfamiliar realm.

In my modernized drawing (see below), I have depicted Venus's birth on a hospital bed. I have depicted Venus to be born by a human-like figure. The ruching sheets by her feet resemble the pearl shell she stands upon in the painting. The newborn baby flies out of her mother's womb and cries in an unfamiliar realm.With doctors on either side of her, perhaps the mother birthing on the bed is self-reflective (a postmodern quality) and Venus is birthed from herself, or emerging from the Sky and Sea.

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

The Principle of his own Subjection: Michel Foucault and Panopticism

Twentieth Century French historian Michel Foucault introduces his power theory of Panopticism in his book Discipline and Punish by using the leper plague as an example of its development. Because the leper was terribly contagious, each member in the plagued town was quarantined and required to, on a daily basis, reveal her face in the window as a means of surveillance: a mechanism confirming those who fell victim to the disease and those who survived. Simultaneously, the separation confined each individual to her own space and established a regulating order to the controversy within the society.

Foucault's theory of Panapticism is based on the Panopticon: a prison building designed by English theorist Jeremy Bentham in 1785. The building was designed in order for an omniscient viewer to be able to see the entirety of the happenings within the building while simultaneously be entirely unseen.

Foucault writes, “The major effect of the Panopticon [is] to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power" (554). Power relations are implemented in Panopticsm by imposing absolute and "understood" rules.

In John Hughes's 1985 cult classic The Breakfast Club, five high school students are forced to spend an entire Saturday in the library serving detention. Detention is a form of punishment where students contemplate the fallacies they have committed without misbehaving further. Foucault would consider detention as one of the "tactics of individualizing disciplines [that] are imposed on the excluded" (553). The students are assigned to sit in the library on a day when there are no other students or teachers present. Principal Richard "Dick" Vernon serves as physical surveillance, but in actuality, he has little power over the students.

In this brief clip, each student sits unsupervised, each occupying himself until falling asleep from boredom. When the Principle discovers the students sleeping, he attempts to use verbal authority by screaming, "WAKE UP!" The students ignore him until he calmly offers a trip the “lavatory.” If the hired authority has no control, then why do the students stay for detention the remainder of the day?

Though they show little respect to the principle, the students adhere to the role of the school as an institution itself. Through their actions throughout the movie, the students reveal their awareness of ideological rules. Regardless, the students break free from the library at various moments to run around the school rebelling against the principle. Although they do not remain seated in their original library seat for eight hours, it is significant to note that the students are submissive to Panopticsm theory. The five students remain within the walls of the school for the entirety of the day confirming the power of the school itself and thus reaffirming Foucault’s idea that, “A real subjection is born mechanically from a fictitious relation. So it is not necessary to use force to constrain the convict to good behavior” (555).

Foucault's theory of Panapticism is based on the Panopticon: a prison building designed by English theorist Jeremy Bentham in 1785. The building was designed in order for an omniscient viewer to be able to see the entirety of the happenings within the building while simultaneously be entirely unseen.

Foucault writes, “The major effect of the Panopticon [is] to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power" (554). Power relations are implemented in Panopticsm by imposing absolute and "understood" rules.

In John Hughes's 1985 cult classic The Breakfast Club, five high school students are forced to spend an entire Saturday in the library serving detention. Detention is a form of punishment where students contemplate the fallacies they have committed without misbehaving further. Foucault would consider detention as one of the "tactics of individualizing disciplines [that] are imposed on the excluded" (553). The students are assigned to sit in the library on a day when there are no other students or teachers present. Principal Richard "Dick" Vernon serves as physical surveillance, but in actuality, he has little power over the students.

In this brief clip, each student sits unsupervised, each occupying himself until falling asleep from boredom. When the Principle discovers the students sleeping, he attempts to use verbal authority by screaming, "WAKE UP!" The students ignore him until he calmly offers a trip the “lavatory.” If the hired authority has no control, then why do the students stay for detention the remainder of the day?

Though they show little respect to the principle, the students adhere to the role of the school as an institution itself. Through their actions throughout the movie, the students reveal their awareness of ideological rules. Regardless, the students break free from the library at various moments to run around the school rebelling against the principle. Although they do not remain seated in their original library seat for eight hours, it is significant to note that the students are submissive to Panopticsm theory. The five students remain within the walls of the school for the entirety of the day confirming the power of the school itself and thus reaffirming Foucault’s idea that, “A real subjection is born mechanically from a fictitious relation. So it is not necessary to use force to constrain the convict to good behavior” (555).

Works Cited

Foucault, Michel. “Discipline and Punish.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 549-565. Print.

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

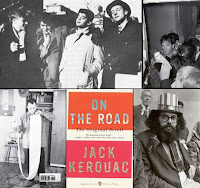

Death is Bliss: On the Road, a Freudian reading

In Jack Kerouac’s novel, On the Road, the narrator Sal shows symptoms of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theories. In the middle of his journey to Western America, Sal wakes up in a motel and says, “I didn’t know who I was – I was far away from home, haunted and tired with travel…I was just somebody else, some stranger, and my whole life was a haunted life, the life of a ghost” (Kerouac 15). Sal reaches his desired destination to California. To his dismay, “the end of America,” does not fulfill his expectations of the West. Thus, he ironically journeys back to where he began: New York. While in New York, Sal is overcome by a familiar feeling of disorientation. He says, “Just about then a strange thing began to haunt me. It was this: I had forgotten something. There was a decision that I was about to make before Dean showed up, and now it was driven clear out of my mind but still hung on the tip of my mind’s tongue” (Kerouac 124). In the motel, Sal becomes forgetful of important matters. In Freud’s essay, The Interpretation of Dreams he offers an explanation for similar behavior. He says, “Forgetting is very often determined by an unconscious purpose and that it always enables one to deduce the secret intentions of the person who forgets” (Freud, 397). Perhaps Sal’s forgetfulness is representative of something that he is not fully aware of. Sal continues, “I couldn’t even tell if it was a real decision or just a thought I had forgotten. It haunted and flabbergasted me, made me sad” (Kerouac 124). Sal has an intense array of emotions caused by something he cannot remember. It is his unconscious that is causing the familiar, yet unidentifiable feelings. Sal searches his memory for the decision he must make. He reveals, “It had to do somewhat with the Shrouded Traveler: a dream I had about a strange Arabian figure that was pursuing me across the desert; that I tried to avoid; that finally overtook me just before I reached the Protective City” (Kerouac 124). It is strange that Sal looks to his dream, filled with the unfamiliar, in order to understand what he consciously cannot remember. Freud would describe Sal’s dream as “the uncanny,” or, when “one does not know where one is” and what is “frightening precisely because it is not known and familiar” (Freud 418). Sal concludes, “The one thing we yearn for in our living days, that makes us sigh and groan and undergo sweet nauseas of all kinds, is the remembrance of some lost bliss that was probably experienced in the womb and can only be reproduced (though we hate to admit it) in death” (Kerouac 124). In a cyclical repetition, Sal undergoes mental instability caused by his unconscious. Sal conforms to Freud’s concept of the phallic stage in childhood: “A little boy will exhibit a special interest in his father; he would like to grow like him and be like him, and take his place everywhere” (Freud 438). Because Sal's father is no longer living, it is no wonder that Sal’s journey around America is unfulfilling and unsettling. Sal’s bliss can only be found where his father is: “in death.”

In Jack Kerouac’s novel, On the Road, the narrator Sal shows symptoms of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theories. In the middle of his journey to Western America, Sal wakes up in a motel and says, “I didn’t know who I was – I was far away from home, haunted and tired with travel…I was just somebody else, some stranger, and my whole life was a haunted life, the life of a ghost” (Kerouac 15). Sal reaches his desired destination to California. To his dismay, “the end of America,” does not fulfill his expectations of the West. Thus, he ironically journeys back to where he began: New York. While in New York, Sal is overcome by a familiar feeling of disorientation. He says, “Just about then a strange thing began to haunt me. It was this: I had forgotten something. There was a decision that I was about to make before Dean showed up, and now it was driven clear out of my mind but still hung on the tip of my mind’s tongue” (Kerouac 124). In the motel, Sal becomes forgetful of important matters. In Freud’s essay, The Interpretation of Dreams he offers an explanation for similar behavior. He says, “Forgetting is very often determined by an unconscious purpose and that it always enables one to deduce the secret intentions of the person who forgets” (Freud, 397). Perhaps Sal’s forgetfulness is representative of something that he is not fully aware of. Sal continues, “I couldn’t even tell if it was a real decision or just a thought I had forgotten. It haunted and flabbergasted me, made me sad” (Kerouac 124). Sal has an intense array of emotions caused by something he cannot remember. It is his unconscious that is causing the familiar, yet unidentifiable feelings. Sal searches his memory for the decision he must make. He reveals, “It had to do somewhat with the Shrouded Traveler: a dream I had about a strange Arabian figure that was pursuing me across the desert; that I tried to avoid; that finally overtook me just before I reached the Protective City” (Kerouac 124). It is strange that Sal looks to his dream, filled with the unfamiliar, in order to understand what he consciously cannot remember. Freud would describe Sal’s dream as “the uncanny,” or, when “one does not know where one is” and what is “frightening precisely because it is not known and familiar” (Freud 418). Sal concludes, “The one thing we yearn for in our living days, that makes us sigh and groan and undergo sweet nauseas of all kinds, is the remembrance of some lost bliss that was probably experienced in the womb and can only be reproduced (though we hate to admit it) in death” (Kerouac 124). In a cyclical repetition, Sal undergoes mental instability caused by his unconscious. Sal conforms to Freud’s concept of the phallic stage in childhood: “A little boy will exhibit a special interest in his father; he would like to grow like him and be like him, and take his place everywhere” (Freud 438). Because Sal's father is no longer living, it is no wonder that Sal’s journey around America is unfulfilling and unsettling. Sal’s bliss can only be found where his father is: “in death.”Works Cited

Freud, Sigmund. "Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego." Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 438-440. Print.

Freud, Sigmund. "The Interpretation of Dreams." Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 397-414. Print.

Freud, Sigmund. "The Uncanny." Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 418-430. Print.

Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. New York: Penguin Books, 1976. Print.

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

What's your sign?

Last semester I touched briefly on the literary theory of Structuralism in my Popular Culture class. We covered Roland Barthes’s book Mythologies and discussed the concept of semiotics. I learned about the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, but not at length. Participating in the Structuralism group for this class furthered my knowledge on the subject and allowed me get a better grasp on signs.

Our discussion is titled, "The Linguistic Turn.” I am happy to say that this experience was truly a group effort. Our group was in clear communication: each person brought creative ideas to the table and contributed just the same. In my opinion and experience, this is rare for a group assignment. Our project is one of structure, and I believe this will show in our presentation this evening. My contribution to the project was piecing together the power point presentation. My group members sent me appropriate information based on their own research about Structuralism and its theoretical movement, historical context, cultural import and the theory's practical uses. I intended to add a playful, yet structured slide-show in order to effectively lead a memorable and fun discussion. Our group ensured that this will indeed be a discussion, and not a lecture. Our intention is to provide a fun learning experience embedding Structuralism into the students’ brains.

My contribution to the project was piecing together the power point presentation. My group members sent me appropriate information based on their own research about Structuralism and its theoretical movement, historical context, cultural import and the theory's practical uses. I intended to add a playful, yet structured slide-show in order to effectively lead a memorable and fun discussion. Our group ensured that this will indeed be a discussion, and not a lecture. Our intention is to provide a fun learning experience embedding Structuralism into the students’ brains.

“What’s your sign?” is a thought provoking card game that we collectively came up with. While the slide-show is intended for individual perception, our group wanted to create an interactive presentation as well. One inevitable goal for tonight is that students who may not have normally worked together will do so in order to participate in the game and ultimately understand the Structuralist concept. I cannot guarantee the shock value that footage of a raw childbirth may bring, but I feel that our assignment will be just as memorable – perhaps ending with laughter instead.

Our discussion is titled, "The Linguistic Turn.” I am happy to say that this experience was truly a group effort. Our group was in clear communication: each person brought creative ideas to the table and contributed just the same. In my opinion and experience, this is rare for a group assignment. Our project is one of structure, and I believe this will show in our presentation this evening.

My contribution to the project was piecing together the power point presentation. My group members sent me appropriate information based on their own research about Structuralism and its theoretical movement, historical context, cultural import and the theory's practical uses. I intended to add a playful, yet structured slide-show in order to effectively lead a memorable and fun discussion. Our group ensured that this will indeed be a discussion, and not a lecture. Our intention is to provide a fun learning experience embedding Structuralism into the students’ brains.